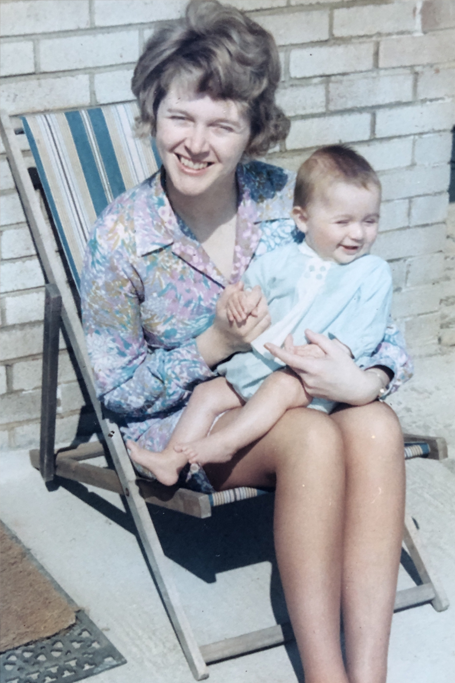

We might imagine our smell preferences are gathered through worldly experience – along with pins in maps, mosquito bites and passport stamps; that we’re constantly expanding our personal taste (and therefore palate of perfumes) as we go. And that might be true – of course our tastes can develop and change – but it turns out these seemingly carefully curated proclivities are most likely formed in early childhood, perhaps even before we’re born – smell being the only sense fully developed in the womb.

Nostrils are formed within the first trimester of a pregnancy, those all-important scent receptors ready by the second trimester. While in the womb, the baby breathes in their mother’s amniotic fluid, which helps them to form a bond by becoming familiar with their mother’s unique scent. Many studies seem to show that what the mother’s eaten during pregnancy even goes on to form the child’s ‘taste’ toward certain flavours, and a new study suggests our particularity toward certain scents may have also been decided, thanks to a process known as ‘imprinting’. According to the report on the science news website eurekalert.org: ‘Exposure to environmental input during a critical period early in life is important for forming sensory maps and neural circuits in the brain.’

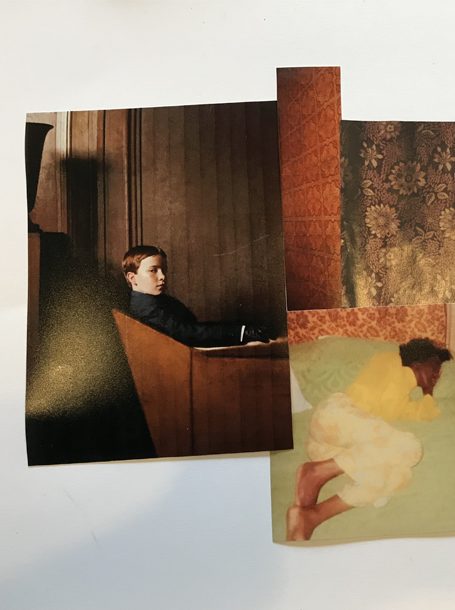

The term ‘imprinting’ basically refers to the phenomenon of certain animals and birds getting ‘fixated on sights and smells they see immediately after being born. In ducklings, this can be the first moving object, usually the mother duck. In migrating fish like salmon and trout, it is the smells they knew as neonates that guides them back to their home river as adults.’ Not enough research has been yet been carried out to prove if we are like the salmon and genetically longing to leap after certain smells; but most of us can say we’ve had that lightning-bolt moment of suddenly being transported to a person, time or place we’d not thought of for years – carried along unbidden in a scent steam of consciousness as we catch a whiff of a familiar fragrance and are taken way back when.

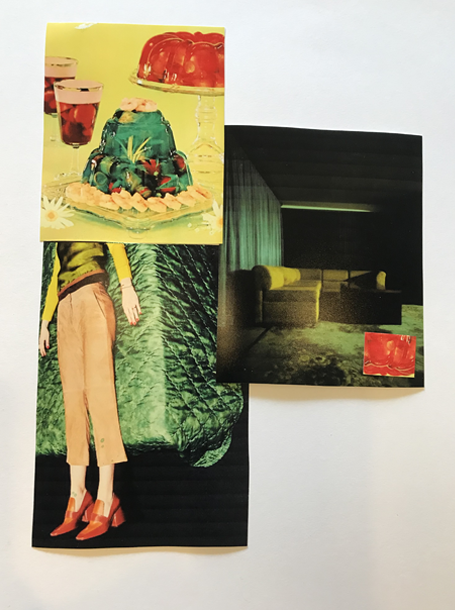

Of course, not everyone’s memories of their mother are so perfect, many having difficult or estranged familial relationships, as seen in Pascale Petit’s powerful, perfume-triggered poem:

My Mother’s Perfume

Strange how her perfume used to arrive long before she did, a jade cloud that sent me hurrying first to the loo, then to an upstairs window to watch for her taxi.

I’d prepare myself by trying to remember her face, without feeling afraid. As she drew nearer I’d get braver until her scent got so strong I could taste the coins in the bottom of her handbag.

And here I am forty years on, still half-expecting her. Though now I just have to open the stopper of an expensive French bottle, daring only a whiff of Shalimar which Jacques Guerlain created from the vanilla orchid vine.

Her ghostly face might shiver like Christ’s on Veronica’s veil – a green-gold blossom that sends me back to the first day of the school holidays, the way I used to practise kissing her cheek by kissing the glass. My eyes scanned the long road for a speck while the air turned amber.

Even now, the scent of vanilla stings like a cane. But I can also smell roses and jasmine in the bottle’s top notes, my legs wading through the fragrant path, to the gloved hand emerging from a black taxi at the gate of Grandmother’s garden. And for a moment I think I am safe.

Then Maman turns to me with a smile like a dropped perfume bottle, her essence spilt.

© 2005, Pascale Petit From: The Huntress Publisher: Seren, Bridgend, 2005 ISBN: 1-85411-396-8

It follows that if, for example, you adored the smell of lavender in your mother’s garden, you’ll likely be drawn to smelling it again throughout your life. But if you had negative associations with that smell from an early age, you’re more likely to avoid it and don’t find it as ‘relaxing’ as most people assume it would automatically be. The same is true for the perfume she chose. Smell is all about culture and context – where we grew up, and how we grew up will partly inform our own adult scent selections.

Scent is truly the closest thing we have to time travel, but not only can we meander through our childhood memories by wearing a particular perfume, we can create new, perhaps kinder, happier ones (if required) by actively concentrating on the fragrances we wear now. Taking time to think about what you’re smelling and how it makes feel can help ‘re-set’ your mood, and actively grow new neural pathways from our noses to our brains. So, you build new perfumes paths to happiness whenever you want if you practice a bit every day. Just jot down a few words and think about the place that perfume reminds you of – what’s the weather like, and what time of day does it suggest? Does it remind you of a dear friend, or a landscape you love?

Another happy thought is that the fragrances we wear now will later become the special scent memory of loved ones to sniff, think of us, and smile.

Skimming Stones

Silvery reflections rippled with aromatic rosemary, the green bergamot a breath of fresh air as mineral notes skim silkily over the lake’s shimmer. Suddenly the air feels full of flowers – iris and wild roses flowing to the rich, deeper greens of velvety moss, earthy patchouli, and a sun-warmed bed of sandalwood and musk.

Hide & Seek

Voluptuous laughter floating in the air on the heady floral breeze of tuberose, a fuzzy hug of peach and ripe plums slowly drifting to luminescent jasmine and exotic ylang ylang hidden in the heart. Nestled beneath, a soft caress of warm skin-like musk, amber and vanilla swathes you in comfort. The kind of fragrance that lingers long after you’ve left the room, and has someone smiling: “ah, I know they were here…”